Read The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger Online

Authors: Richard Wilkinson,Kate Pickett

Tags: #Social Science, #Economics, #General, #Economic Conditions, #Political Science, #Business & Economics

The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger (5 page)

To avoid being accused of picking and choosing our measures, our approach in this book has been to take measures provided by official agencies rather than calculating our own. We use the ratio of the income received by the top to the bottom 20 per cent whenever we are comparing inequality in different countries: it is easy to understand and it is one of the measures provided ready-made by the United Nations. When comparing inequality in US states, we use the Gini coefficient: it is the most common measure, it is favoured by economists and it is available from the US Census Bureau. In many academic research papers we and others have used two different inequality measures in order to show that the choice of measures rarely has a significant effect on results.

DOES THE AMOUNT OF INEQUALITY MAKE A DIFFERENCE?

Having got to the end of what economic growth can do for the quality of life and facing the problems of environmental damage, what difference do the inequalities shown in Figure 2.1 make?

It has been known for some years that poor health and violence are more common in more unequal societies. However, in the course of our research we became aware that almost all problems which are more common at the bottom of the social ladder are more common in more unequal societies. It is not just ill-health and violence, but also, as we will show in later chapters, a host of other social problems. Almost all of them contribute to the widespread concern that modern societies are, despite their affluence, social failures.

To see whether these problems were more common in more unequal countries, we collected internationally comparable data on health and as many social problems as we could find reliable figures for. The list we ended up with included:

• level of trust

• mental illness (including drug and alcohol addiction)

• life expectancy and infant mortality

• obesity

• children’s educational performance

• teenage births

• homicides

• imprisonment rates

• social mobility (not available for US states)

Occasionally what appear to be relationships between different things may arise spuriously or by chance. In order to be confident that our findings were sound we also collected data for the same health and social problems – or as near as we could get to the same – for each of the fifty states of the USA. This allowed us to check whether or not problems were consistently related to inequality in these two independent settings. As Lyndon Johnson said, ‘America is not merely a nation, but a nation of nations.’

To present the overall picture, we have combined all the health and social problem data for each country, and separately for each US state, to form an Index of Health and Social Problems for each country and US state. Each item in the indexes carries the same weight – so, for example, the score for mental health has as much influence on a society’s overall score as the homicide rate or the teenage birth rate. The result is an index showing how common all these health and social problems are in each country and each US state. Things such as life expectancy are reverse scored, so that on every measure higher scores reflect worse outcomes. When looking at the Figures, the higher the score on the Index of Health and Social Problems, the worse things are. (For information on how we selected countries shown in the graphs we present in this book, please see the Appendix.)

We start by showing, in Figure 2.2, that there is a very strong tendency for ill-health and social problems to occur less frequently in the more equal countries. With increasing inequality (to the right on the horizontal axis), the higher is the score on our Index of Health and Social Problems. Health and social problems are indeed more common in countries with bigger income inequalities. The two are extraordinarily closely related – chance alone would almost never produce a scatter in which countries lined up like this.

Figure 2.2

Health and social problems are closely related to inequality among rich countries.

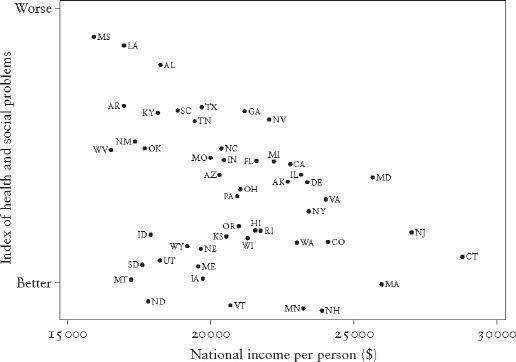

To emphasize that the prevalence of poor health and social problems in whole societies really is related to inequality rather than to average living standards, we show in Figure 2.3 the same index of health and social problems but this time in relation to average incomes (National Income per person). It shows that there is no similarly clear trend towards better outcomes in richer countries. This confirms what we saw in Figures 1.1 and 1.2 in the first chapter. However, as well as knowing that health and social problems are more common among the less well-off within each society (as shown in Figure 1.4), we now know that the overall burden of these problems is much higher in more unequal societies.

Figure 2.3

Health and social problems are only weakly related to national average income among rich countries.

To check whether these results are not just some odd fluke, let us see whether similar patterns also occur when we look at the fifty states of the USA. We were able to find data on almost exactly the same health and social problems for US states as we used in our international index. Figure 2.4 shows that the Index of Health and Social Problems is strongly related to the amount of inequality in each state, while Figure 2.5 shows that there is no clear relation between it and average income levels. The evidence from the USA confirms the international picture. The position of the US in the international graph (Figure 2.2) shows that the high average income level in the US as a whole does nothing to reduce its health and social problems relative to other countries.

We should note that part of the reason why our index combining data for ten different health and social problems is so closely related to inequality is that combining them tends to emphasize what they have in common and downplays what they do not. In Chapters 4–12 we will examine whether each problem – taken on its own – is related to inequality and will discuss the various reasons why they might be caused by inequality.

Figure 2.4

Health and social problems are related to inequality in US states.

Figure 2.5

Health and social problems are only weakly related to average income in US states.

This evidence cannot be dismissed as some statistical trick done with smoke and mirrors. What the close fit shown in Figure 2.2 suggests is that a common element related to the prevalence of all these health and social problems is indeed the amount of inequality in each country. All the data come from the most reputable sources – from the World Bank, the World Health Organization, the United Nations and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and others.

Could these relationships be the result of some unrepresentative selection of problems? To answer this we also used the ‘Index of child wellbeing in rich countries’ compiled by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). It combines forty different indicators covering many different aspects of child wellbeing. (We removed the measure of child relative poverty from it because it is, by definition, closely related to inequality.) Figure 2.6 shows that child wellbeing is strongly related to inequality, and Figure 2.7 shows that it is not at all related to average income in each country.

Figure 2.6

The UNICEF index of child wellbeing in rich countries is related to inequality.

Figure 2.7

The UNICEF index of child wellbeing is not related to Gross National Income per head in rich countries.

SOCIAL GRADIENTS